So I come back to Business Model Generation for another go. Each time I try to write about this book, I end up going off in another direction as different aspects of what is in the book catch my attention.

So I come back to Business Model Generation for another go. Each time I try to write about this book, I end up going off in another direction as different aspects of what is in the book catch my attention.

A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.

And, of course, it is our value and values that we often hold in the third sector as the things that set us apart. If you have doubts about the ethics of running a charity as a business, maybe jump over to Stakeholder Value first and, indeed, Who are our Customers?

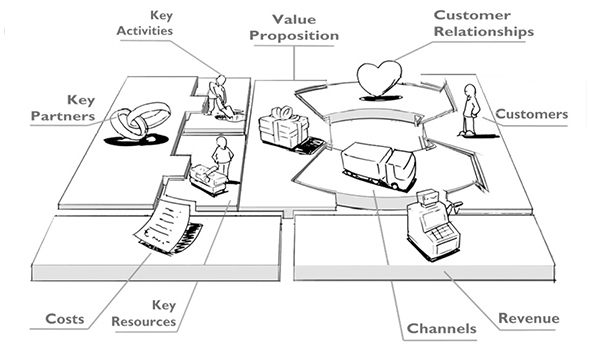

The Business Model Canvas is a way of describing what you do, who you do it for, who benefits, how you do it, how you pay for it, who you need and who can help you along the way; that’s quite a lot to fit on one piece of paper!

I found the canvas while investigating the production of a business plan for the Irish Association of Youth Orchestras and it was a full seven years before I completed it; due mainly to the range of activities we engage in, and stakeholders we serve. I eventually had to have five different pages to describe everyone and everything so that each made sense on its own. At least we now have the full set of ‘customer perspectives’ though.

As you can see, the canvas centres around the idea of the ‘value proposition’. It took me some time to come to grips with this – mostly because the term value is so devalued these days. Equating it to ‘customer need’ doesn’t feel so right in a world where all our time-saving devices seem to leave us with less, rather than more, time. Being ‘customer focussed’ is also something that I am inherently uncomfortable with when, especially in the arts, we are often pursuing the realisation of a vision rather than providing goods and services to customers in exchange for their money. If we have to change what we do so substantially that it becomes different from the original vision just in order to satisfy the ‘customer’, then we’re probably doing it wrong!

However, the canvas and ideas contained in it are sufficiently flexible to deal with different motivations as well as different kinds of business. We have an idea that can change the world! What and who do we need to make that idea a reality? Who can help us? What will it cost? Who will pay for it? At the end of the day we can lay out all aspects of production and then start investigating who will pay for it – are there customers? Can we package it and sell it to different people in different ways?

One of the most interesting, and often confusing aspects, is the idea of the multi-platform market. Essentially this is a business model in which some ‘customers’ subsidise the participation of others. The most well-known of these would be newspapers and magazines. The readership purchase the publications at a price below the production price (all the way down to free). The advertisers pay the publishers for access to the readership, thus making the whole enterprise profitable.

In the third sector, we are often (possibly always) operating in a multi-platform market. If we receive funding or donations to provide services to individuals, the individuals receive the services at a subsidised price whilst the funders and donors make up the difference. What do the latter get out of it? In terms of government, they get necessary services provided at a cost lower than they could provide themselves whilst keeping the people who do the work off their own books. Unfortunate but true; their funding buys expendability. For donors and trusts, they see that they are doing good in the world – that’s why they exist; to see that the work is done rather than necessarily, to do the work themselves.

I continue to be a bit confused about where to put donors and funders in the model. Sometimes they feel like the key partners, sometimes just customers. The latter does help make my life a whole lot easier. I have seen plenty of emotive reactions to funding decisions over the years with blame laid at the funder’s door. Treating funding applications as tenders delivered to potential customers feels a lot easier to me. I can focus on how my proposals do or don’t fulfil the remit of the funder; I can decide how to best package it in order to have the correct appearance. As I was told years ago on the ‘For Impact‘ training through Business to Arts – ‘You’re in sales. Get over it!’ I am and I have.

Do we have the potential for unethical behaviour here? Yes, we do! There is the possibility that companies will move their purpose to find the money rather than trying to move the money to serve the purpose – meeting customer needs rather than pursuing the mission. However, putting the value proposition at the heart of the canvas makes it really clear if that proposition is diverging from the mission that gave rise to it. It may well be that adopting a clear business model is a safeguard against mission drift rather than an encouragement to it – that it will help organisations stay on the ethical straight and narrow and reinforce their commitment to their mission rather than the reverse.

I can never conclusively put my finger on it, but I think that, in the third sector, there is a feeling that for-profit versus not-for-profit is an opposition of unethical versus ethical. I remember in an earlier edition of A Practical Guide for Board Members of Arts Organisations, it was stated in two separate places that ‘arts organisations are not businesses’. In the second instance, it said, ‘The measure of success in arts terms centres on values and not on profits’. True, but a zero profit-margin target and mission-based goals do not make a company ‘not a business’ – not in my world anyway.

So, to wrap up, this is a book that I have found really useful in terms of running a charity and in my involvement with other charities. It has allowed me to clarify a large range of ambitions, activities and stakeholders into something manageable that I can make progress on each aspect each day. It has allowed me to focus on the outcomes of my work in the short-term and the long-term, the short-term suiting the client-customers and the long-term suiting the funder-clients. In my own work, I don’t have any conflict between the interests of the two but it’s good to be able to see and state them clearly. It has also allowed me to walk around the world and see clearly how commercial companies are making their money and see correlations between how they work and how I do; allowing me to see into their machinations from their store-fronts and see if there is anything they are doing that I could incorporate into what I do.

Possibly more questions raised than answers provided in this post!? The best thing to do is see for yourself and understand that, although aimed mainly at for-profit businesses, this is a method that can be applied to any form of value-creation – not just the money kind. You can download a preview of the book here to see if you like it. It’s definitely worth the tree for a paper copy too.